David Keil talks chaturanga for a bit, the posture that is most often blamed for creating shoulder pain.

http://www.yoganatomy.com/just-blame-chaturanga-by-david-keil-2010/ – David Keil

I hear it in so many workshops. Chaturanga hurt my shoulder! This is said as if chaturanga is a living breathing entity that has the ability to raise up and hurt people. Actually, I hear this about many things, whether they are postures or methods. In other words as an Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga teacher I hear that Ashtanga injures people. What can I say, it’s human nature to blame something or someone else. As if a posture or method actually does something to us.

The truth is, the pose doesn’t even exist until we actually do it. Key word is WE, that is, we, are doing the pose. Sometimes we don’t do it correctly, or we have no focus while doing it, or we’re instructed poorly, it’s even possible that it’s just karma. Who knows exactly why, but I feel like I do know that it’s never the yoga posture (or method), it’s us doing it that causes problems. I often say that the pose doesn’t even exist until we are performing it.

Let’s talk chaturanga for a bit, the posture that is most often blamed for creating shoulder pain.

The Anatomy

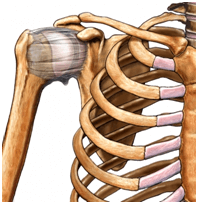

The shoulder girdle is complex, even sometimes referred to as the shoulder complex. It is a very versatile and mobile structure and made up of more than one joint. Most of the time we simply say shoulder and this is sufficient for most conversations, but of course, it’s me, DK, A.K.A “the bone man” on this end trying to elevate the conversation and reminding everyone to see a little bit more of the bigger picture.

When we say shoulder we’re being vague about what we’re talking about. On the technical side we’re talking about the shoulder joint and when we say shoulder we mean the relationship between the scapula and the humerus (glenohumeral joint). But, this is just one of the relationships in the shoulder girdle.

We also have the clavicle or collarbone that attaches to the sternum on one end and the scapula on the other. The end that attaches to the sternum is the single place where the upper extremity (arm) attaches onto the axial skeleton (spine, skull and ribs). That joint is a whole other conversation to have in a different article. Let’s just say, it’s also complex and has forces created on it from the rest of the shoulder girdle.

The end of the collarbone that attaches onto the scapula is called the AC joint, which is short for AcromioClavicular joint. This means that the clavicle is tied to the scapula via ligaments and any scapular movement includes clavicular movement and vice versa.

When the actual shoulder joint (glenohumeral joint) moves, it can do so independently of these other two bones and joints. However, when we reach the end of range of motion at the shoulder joint basically bringing the humerus parallel to the floor in a forward (flexion) or sideways (abduction) direction, further movement then includes movements of these other two bones. There could be a small percentage of people who are an exception to this, but they’re hard to find.

Looking at Chaturanga and Shoulder Function

So when we look at a movement like chaturanga, we are not moving out of the normal range of motion of the shoulder joint. However, in order for the shoulder joint to function optimally, the rest of the shoulder girdle must be stabilized for efficient movement of the humerus.

By efficient, I mean movement that doesn’t over burden or stress the muscles that move this joint. The great debate on chaturanga is where to put those pesky scapulae (plural form). Perhaps a more important question to ask before you try to make someone hold their scapulae in a particular position is, do they actually have the strength to do so in the muscles that stabilize the scapula? If they don’t, what does this mean for how the shoulder joint itself is going to have to function? What kind of stresses will it have to take on?

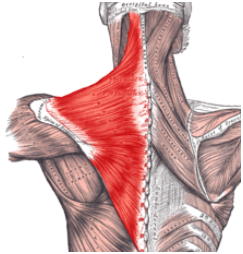

Here are some of the main players in controlling or stabilizing the scapulae:

– Trapezius

– Rhomboids

– Pectoralis minor

– Serratus anterior

When you see a shoulder not in the “right” position in a chaturanga, it’s not because of the shoulder, it’s because the scapulae are not, or cannot be held in the appropriate place. Why not? Because the muscles that create the stability of the scapulae are either not strong enough or not patterned correctly to make this possible.

This can potentially lead to a strain of various muscles at the actual shoulder joint such as:

– Rotator cuff muscles

– Deltoids

– Bicep tendons

There are other issues at play here as well, including where the shoulders line up with the hands. The further forward the shoulders are from the hands, the more strain ends up in the shoulders. This happens because bulk of the upper body weight is too far out in front to be supported by the hands under it. Imagine holding a twenty pound weight directly over your shoulder. That shouldn’t be a problem. Now move it forward just a few inches and gravity starts to work on your shoulder in a very different way.

As far as general alignment rules for stacking joints is concerned, don’t apply it to the wrist and the elbow for chaturanga. OK, there may be a few people who are an exception to this last statement, but for most people, putting their elbows over their wrists in chaturanga will place way too much strain on the shoulder. Not to mention, it also increases the wrist angle and can cause problems there too. Most people should have their elbow slightly behind their wrist, which brings the center of their chest and their weight closer to the line between their two hands.

All of this is assuming that somehow chaturanga lives in a vacuum of practice. It doesn’t. If you’re working with someone with shoulder pain, you should also look at the yoga posture that follows chaturanga most commonly, which is upward facing dog. I often see a pattern of chaturanga that has people forward on their toes and in their shoulders and the up dog that follows tends to put the shoulders way out in front of the hands underneath it. This has a series of effects that play themselves out. One is, it puts a lot of stress on the wrist. Secondly, it has a tendency to put stress in the back by trying to make the back bending aspect of up dog happen. This also tends to lead to a buttocks that is over tightened for the wrong reasons. Thirdly, it puts a load of stress on the shoulders once again.

Another common problem I see is people taking on too much practice too quickly. This by itself can be enough to inflame a number of areas in the body, especially the shoulders. This is especially true if you’re practicing one of the myriad styles of vinyasa yoga.

Conclusion

If you’re experiencing shoulder pain or have students who are, take a moment and observe them. Don’t just try to make them do it differently because it doesn’t look right, look at the bigger picture. Look at the line they’re creating between the front of their shoulder and their hands beneath it. Also take into consideration their general strengths and weaknesses in the practice and whether or not they’re simply doing too much at the moment.