The practice of drishti is a gazing technique that develops concentration—and teaches you to see the world as it really is.

By David Life – http://www.yogajournal.com/article/philosophy/the-eye-of-the-beholder/ Photo: Joey Miles http://www.ashtangabrighton.com/ashtanga-practice-and-fatherhood-joey-miles

We humans are predominantly visual creatures. As every yoga practitioner has discovered, even during practice we find ourselves looking at the pose, outfit, or new hairstyle of the student on the next mat. We stare out the window or at the skin flaking between our toes, as though these things were more interesting than focusing on God realization. And thwack! Where our eyes are directed, our attention follows.

Our attention is the most valuable thing we have, and the visible world can be an addictive, overstimulating, and spiritually debilitating lure. The habit of grasping at the world is so widespread that the spiritual teacher Osho coined a term for it: “Kodakomania.” If you have any doubt about the power of the visual image and the value of your attention, just think of the billions of dollars the advertising industry spends on photography every year!

When we get caught up in the outer appearance of things, our prana (vitality) flows out of us as we scan the stimulating sights. Allowing the eyes to wander creates distractions that lead us further away from yoga. To counteract these habits, control and focus of the attention are fundamental principles in yoga practice. When we control and direct the focus, first of the eyes and then of the attention, we are using the yogic technique called drishti.

The increasing popularity and influence of the Ashtanga Vinyasa method of yoga, taught for more than 60 years by Sri K. Pattabhi Jois, have introduced drishti to thousands of practitioners. On a simple level, drishti technique uses a specific gazing direction for the eyes to control attention. In every asana in Ashtanga, students are taught to direct their gaze to one of nine specific points.

In Urdhva Mukha Svanasana (Upward-Facing Dog Pose), for instance, we gaze at the nose tip: Nasagrai Drishti. In meditation and in Matsyasana (Fish Pose), we gaze toward the Ajna Chakra, the third eye: Naitrayohmadya (also called Broomadhya) Drishti. In Adho Mukha Svanasana (Downward-Facing Dog Pose), we use Nabi Chakra Drishti, gazing at the navel. We use Hastagrai Drishti, gazing at the hand, in Trikonasana (Triangle Pose). In most seated forward bends, we gaze at the big toes: Pahayoragrai Drishti. When we twist to the left or right in seated spinal twists, we gaze as far as we can in the direction of the twist, using Parsva Drishti. In Urdhva Hastasana, the first movement of the Sun Salutation, we gaze up at the thumbs, using Angusta Ma Dyai Drishti. In Virabhadrasana I (Warrior Pose I), we use Urdhva Drishti, gazing up to infinity. In every asana, the prescribed drishti assists concentration, aids movement, and helps orient the pranic (energetic) body.

The full meaning of drishti isn’t limited to its value in asana. In Sanskrit, drishti can also mean a vision, a point of view, or intelligence and wisdom. The use of drishti in asana serves both as a training technique and as a metaphor for focusing consciousness toward a vision of oneness. Drishti organizes our perceptual apparatus to recognize and overcome the limits of “normal” vision.

Our eyes can only see objects in front of us that reflect the visible spectrum of light, but yogis seek to view an inner reality not normally visible. We become aware of how our brains only let us see what we want to see—a projection of our own limited ideas. Often our opinions, prejudices, and habits prevent us from seeing unity. Drishti is a technique for looking for the Divine everywhere—and thus for seeing correctly the world around us. Used in this way, drishti becomes a technique for removing the ignorance that obscures this true vision, a technique that allows us to see God in everything.

Of course, the conscious use of the eyes in asana isn’t limited to the Ashtanga Vinyasa tradition. In Light on Pranayama, for example, B.K.S. Iyengar comments that “the eyes play a predominant part in the practice of asanas.” Besides its use in asana, drishti is applied in other yogic practices. In the kriya (cleansing) technique of trataka, or candle gazing, the eyes are held open until tears form. This technique not only gives the eyes a wash but also challenges the student to practice overriding unconscious urges—in this case, the urge to blink.

Sometimes in meditation and pranayama practices the eyes are held half-opened and the gaze is turned up toward the third eye or the tip of the nose. In the Bhagavad Gita (VI.13) Krishna instructs Arjuna, “One should hold one’s body and head erect in a straight line and stare steadily at the tip of the nose.” When using the inner gaze, sometimes called Antara Drishti, the eyelids are closed and the gaze is directed in and up toward the light of the third eye. As Iyengar puts it, “The closure of the eyes … directs the sadhaka (practitioner) to meditate upon Him who is verily the eye of the eye… and the life of life.”

Drishti Tips

As with many spiritual techniques, with drishti there is a danger of mistaking the technique for the goal. You should dedicate your use of the body (including the eyes) to transcending your identification with it. So when you look at an object during your practice, don’t focus on it with a hard gaze. Instead, use a soft gaze, looking through it toward a vision of cosmic unity. Soften your focus to send your attention beyond outer appearance to inner essence.

You should never force yourself to gaze in a way that strains your eyes, brain, or body. In many seated forward bends, for example, the gazing point may be the big toes. But many practitioners, at certain stages in their development, must take care not to create such an intense contraction of the back of the neck that this discomfort overwhelms all other awareness. Rather than forcing the gaze prematurely, you should allow it to develop naturally over time.

In general, practitioners should use the various bahya (external) gazing points during more externally oriented yoga practices, including asanas, kriyas (cleansing practices), seva (the service work of karma yoga), and bhakti (devotion); use the antara (internal) gaze to enhance contemplative and meditative practices. If you find yourself closing the eyes during any practice and focusing on the dramas or perplexities of life instead of being able to maintain a neutral, detached focus, re-establish an outer gaze. On the other hand, if the outer gaze becomes a distraction to your concentration, perhaps an inner-directed correction is necessary.

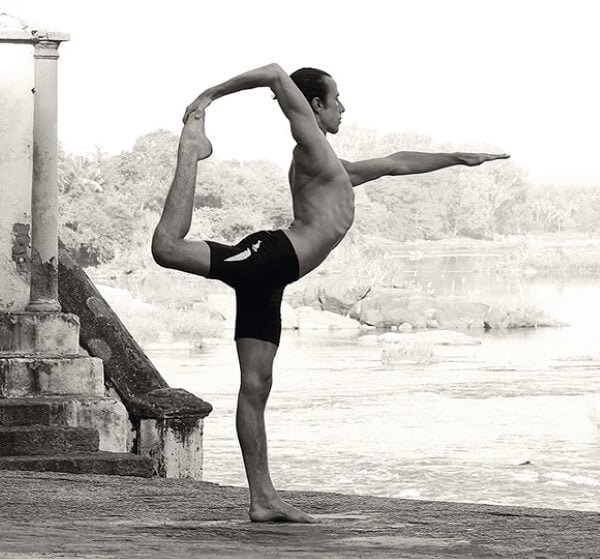

A fixed gaze can help enormously in balancing poses like Vrksasana (Tree Pose), Garudasana (Eagle Pose), Virabhadrasana III (Warrior Pose III), and the various stages of Hasta Padangusthasana (Hand-to-Big-Toe Pose). By fixing the gaze on an unmoving point, you can assume the characteristics of that point, becoming stable and balanced. More importantly, constant application of drishti develops ekagraha, single-pointed focus. When you restrict your visual focus to one point, your attention isn’t dragged from object to object. In addition, without these distractions, it’s much easier for you to notice the internal wanderings of your attention and maintain balance in mind as well as body.

Drishti—The True View

Throughout the history of yoga, clear, true perception has been both the practice and goal of yoga. In the Bhagavad Gita, Lord Krishna tells his disciple, Arjuna, “You are not able to behold me with your own eyes; I give thee the divine eye, behold my Lordly yoga” (11.8). In the classic exposition of yoga, the Yoga Sutra, Patanjali points out that in viewing the world, we tend not to see reality clearly, but instead get deluded by the error of false perception. In Chapter II, verse 6, he says that we confuse the act of seeing with the true perceiver: purusha, the Self. He continues, in verse 17, to say that this confusion about the true relationship between the act of seeing, the object seen, and the identity of the Seer is the root cause of suffering. His cure for this suffering is to look correctly into the world around us.

How are we to do this? By maintaining a prolonged, continuous, single-pointed focus on the goal of yoga: samadhi, or complete absorption into purusha. The practice of drishti gives us a technique with which to develop single-pointed concentration of attention. The hatha yogi uses a kind of “x-ray vision” comprised of viveka (discrimination between “real view” and “unreal, apparent view”) and vairagya (detachment from a mistaken identification with either the instrument of seeing or that which is seen). This basic misidentification is called avidya (ignorance), and its counterpart, vidya, is our true identity.

The bhakti yogi uses drishti in a slightly different way, constantly turning a loving, longing gaze toward God. Through imagination the vision of the Divine appears in the form of Krishna, and the whole world becomes prasad (holy nourishment). In both cases, drishti provides a kind of enhanced yogic vision that allows us to see past outer differences (asat, in Sanskrit) to inner essence or Truth (sat). If we remove ignorance through these practices, we can then see through deception and delusion.

When we charge our eyes with yogic vision, we see our true Self. As we gaze at others, we perceive our own form, which is Love itself. We no longer see the suffering of other beings as separate from our own; our heart is filled with compassion for the struggling of all these souls to find happiness. The yogic gaze emerges from an intense desire to achieve the highest goal of unitive consciousness, rather than from egoistic motives that create separation, limitation, judgment, and suffering.

Like all yogic practices, drishti uses the blessed gifts of a human body and mind as a starting place for connecting to our full potential—the wellspring that is the source of both body and mind. When we clear our vision of the covering of habits, opinions, ideas, and their projections about what is real and what is false, we gaze beyond outer differences toward the absolute Truth.