In this seventh of 8 articles, we continue along the journey of sun salutations and explore the next movement – upward facing dog.

http://www.yoganatomy.com/upward-facing-dog-sun-salutations-part-7/ – David Keil

Before we move into upward facing dog

In Article 6 of this series we took a closer look at chaturanga. Here, we are going to move forward quite literally into upward facing dog. Before we move on, I’d like to address some left over details from the the last article on chaturanga. Some questions arose about chaturanga such as:

Is it necessary that everyone be able to do/achieve chaturanga? No.

Is it a good long term pattern? We don’t really know the answer to this. Yoga asana in the way that we practice it is a fairly recent experiment.

Having said that, ALWAYS look at what you’re practicing in the context of who you are, why you practice, and where you are trying to get to. The same context applies to your students if you’re teaching. If you’re taking up yoga later in life or are teaching a 72 year old who has never done physical activity, chaturanga may be out of reach and possibly even inappropriate. You or they may even get a pass from having to do chaturanga altogether. But, you never know what’s possible because we’re all different.

My point is that you should pay attention to converging histories. Without seeing our students in the context of who they are and where they are trying to go, it’s difficult to make the right decisions. If your demographic doesn’t fit with doing certain yoga postures, DON’T DO IT!

The other point I want to address from the last Sun Salutation article is the body, elbow, wrist component. It’s an important one. I have heard many stories about what the right alignment is for these three areas. Statements such as: NEVER let your body go below your elbows. ALWAYS keep your elbows at ninety degrees. Your elbow SHOULD be over your wrist.

In my opinion, they are all true and false at the same time. All could be right or wrong depending once again on who’s doing it! For instance, if you have a strong core of the upper body, which in my mind primarily means the serratus anterior, your shoulder girdle is stabilized, so chaturanga should be fine. If you also have triceps that are strong enough, then letting your body and shoulders go below the elbow is not necessarily a problem.

If on the other hand, these fundamental strengths are not in place and your body must compensate, then it totally makes sense NOT to go below the elbow. Stay higher until the strength comes.

Related to this is whether or not the elbows should be at ninety degrees and whether they should be directly over the wrists. Although the logic of maintaining the joint at ninety degrees is generally applied to the knee joint, the elbow is a different joint. This is often applied to the knee because the knee is more vulnerable generally speaking. Yes, they are both classified as hinge joints, but only the elbow is a “true” hinge. The knee also has the ability to rotate, once it is bent ten degrees or more. Elbow rotation happens at a separate joint.

In addition to that, the ankle under the knee is a very different joint from the wrist. In chaturanga, it’s the wrist living under the elbow. When applying a rule such as, the elbow must be over the wrist, when this logic is based on the general rule of the knee, it doesn’t always make sense. In other words, ninety degrees in the wrist is potentially more problematic than ninety degrees at the ankle. For some people, ninety degrees at the wrist is painful. In order to reduce the wrist angle, they will have to change the stacking of the elbow above it. To reduce wrist angle you would have to send the elbow behind the wrist joint.

Moving into Upward Facing Dog

All of the above mentioned points about wrist, elbow alignment in chaturanga have a direct impact on the movement that often follows chaturanga, which is an upward facing dog.

The importance of where the hands are in relationship to the elbow naturally means that there is also a relationship of distance between the hands and the feet and how far apart they are from one another.

Why is this important? Well, the hands and the feet are also the foundation of upward facing dog. We will have to include a key piece of anatomy as we move into what is often the very first back bending yoga posture of our practice. That is, the flexibility of the spine. This is important because depending on how flexible your spine is, it may or may not fit into the foundation you have given it as you move from chaturanga to upward facing dog.

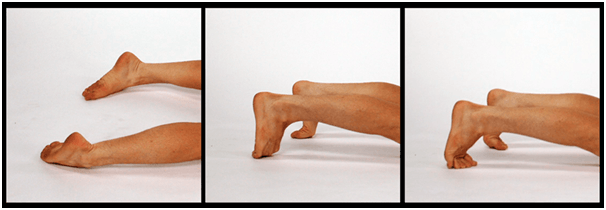

The other factor is the actual technique of moving from one to the other. That is, do you roll over your toes? Do you flip your feet to place the tops of them on the floor? Do you slide your toes back a little bit and then flip over them? Does it change as your body warms up and the flexibility in your spine increases?

Once again, I will avoid telling you which is right and which is wrong because they are all right and wrong depending on who you are and what your converging histories are. If you’re generally more flexible, then rolling over toes might work out just fine for you from the beginning of your practice. If you’re generally tighter, or particularly tight in your spine, you may have to flip or slide your feet to INCREASE the distance between the hands and the feet from where they were while you were in chaturanga. This way, you end up with the correct distance for you in upward facing dog.

Why is all of this so important for upward facing dog? Because if the distance between your hands and feet is too short and you also have an inflexible spine, it’s likely that your shoulders are well out in front of your wrist by the time you’ve finished your up dog. If your shoulders are too far out in front of your wrists, you are now compressing the wrists, probably beyond ninety degrees.

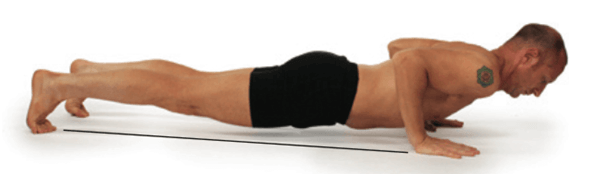

LINE REPRESENTS THE DISTANCE BETWEEN HANDS AND FEET.

The other common problems that come from too short of a foundation are strained shoulders, tight neck, and overly tight buttocks. By overly tight buttocks, I mean one that is not purposely engaged, but instead, grabbing on for dear life to prevent you from collapsing. Lower back muscles are then often locked in stabilization along with the buttocks.

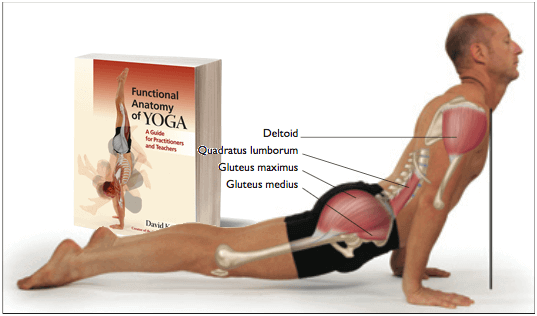

SHOULDER ARE TOO FAR FORWARD, LIKELY TO RESULT IN COMPENSATIONS AND COMPRESSIONS.

Foot Compensations

The feet compensate in a number of ways in up dog to help make up the shortened distance. Personally I find this one problem, the wrong distance between hands and feet, is the main culprit in the myriad of compensations in the feet, shoulders, and neck.

The compensation might happen by being up on the toes in either direction or by splaying the feet out with the heels pointed out toward the edges of the mat. Both are often reflections of not enough distance between the hands and the feet. The shoulders being overly squeezed behind the back is another way of compensating to get the shoulders back in alignment with the wrists.

SHOWS THE VARIETY OF FOOT COMPENSATIONS POSSIBLE.

Depending on the student, the compensation of squeezing the shoulders can unground the hands and result in the person placing too much weight on the outer edges of the hands. Another part of this is the commonly heard instruction to externally rotate the upper arms so that the inside of the elbow is pointing forward. I’ve never been clear on what this is an indication of?

Shoulder Compensations

The shoulder compensation can also lead to one of the most egregious of the problems in upward facing dog which is the scrunching of the shoulders. I often see two things tie together for this one. First is the locking and twisting of the elbow and upper arm. The second is the lack of understanding the core of the upper body. I usually refer to the serratus for that, but in this case, I’ll add on to it.

Because our spine is more vertical, serratus has less effect on the relationship between the rib cage and the scapulae. Although it seems like we need to move our scapulae down our back in depression, this isn’t technically what happens. The scapulae are in a sense unable to move up or down because they are connected to our arms and hands which are on the floor. What technically happens when we push into the floor is that we activate the depressors of the scapulae. However, instead of the scapulae moving down, the rib cage between them is lifted up!

This is the work of two main muscles, the pectoralis minor which is quite close in proximity to our serratus anterior, and the lower part of our trapezius muscle. There might be some help from someone else, possibly lower fibers of pectoralis major, but not much. Looking in the right places for the action to be generated is an important part of relating anatomy to your practice. Look closely the next time you do your up dog.

Personally, I keep upward facing dog about the spine. I find that all of these compensations are distractions from that primary aim. If you do them and they add to your spinal movement, then keep doing them.

The simple correction is to move the hands and the feet further away from one another. Often it’s just a small amount. This often allows the shoulders to come back over the wrists. For me, if we dropped a plumb line down from the front edge of the shoulder in upward facing dog, that plumb line would land somewhere in front of the crease in the wrist and the first set of knuckles (metacarpophalangeal joints).

Conclusion

Upward facing dog should be seen as part of a larger view of practice and how it fits into and integrates with all other backbending type postures. That is, there is an underlying anatomical pattern that feeds all backbends. Training your spine to move, be open, and in control during one of them naturally feeds all of the others.

Take a look and check how you move from chaturanga to upward facing dog. Does it change as your body warms up? Where are your shoulders in upward facing dog? Remember, if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.