In this sixth of 8 articles, we continue along the journey of sun salutations and explore the next movement – lowering into chaturanga

http://www.yoganatomy.com/sun-salutations-part-6-lowering-into-chaturanga/ – David Keil

Landing and Lowering into Chaturanga

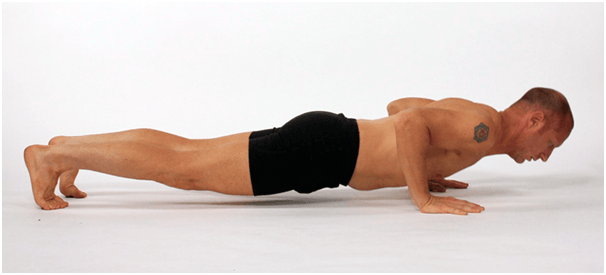

In the last article in this series, we looked at the jump back from the looking up position. In the next step, you have choices. Heck, in the last step you had choices; you could easily have stepped back. When you jumped back, you could have done so with straight arms and landed in high plank or you could have jumped back and landed in chaturanga.

Which brings us to the next piece of Sun Salutations: Should you land in a high plank or in chaturanga?

As usual there are arguments to be made for both. As I typically do, I see them both in a larger context of how either one is going to be creating a pattern of movement. The more important question that you should ask yourself is which patterns are you trying to cultivate and why?

High Plank or Chaturanga

It seems many people, at least in the Ashtanga world default to jumping back into chaturanga. It is after all the most traditional approach. I would even suggest that this is an ideal that we should head for if the right patterns are in place. It’s reason enough for me that tradition is important. Therefore if you want to aim toward the tradition, jump back into chaturanga. However, if the right patterns are not in place, you may become a victim of chaturanga.

You’re probably well aware of the anatomical side of my thinking and the context of practice that we are working in. This leads me into my own stories about why people should jump back into high plank and then lower down, especially beginners. Yes, I have a bias.

The beginners are often in need of developing the pattern I’ve been talking about in Part 4 and Part 5 of this Sun Salutation series. That pattern is the development of:

– The relationship of hand to floor.

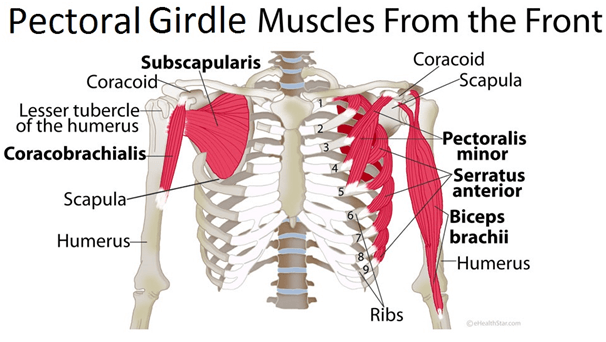

– Development of the serratus anterior muscle.

– Creating a strong and stable shoulder girdle.

– Connecting to core and bandha (not exactly the same thing).

Me and My Bias

Since I am biased toward landing in high plank, most of my pros are going to land on that side. But don’t get me wrong. It’s not that I think landing in chaturanga is wrong or bad, I’m just focused on developing good anatomical patterns that support it first.

The truth is, if you land improperly in either version, you can cause problems. If done rigidly, landing in both high plank or chaturanga can be jarring. If they are done too loosely, then there is that “sag” that happens in the lower back and SI joint area. I usually see this in two parts. The first is it usually means that the relationship to controlling the movement is in place. This is related to the idea of core. The second reason is that there is a directional problem to how the feet hit the floor and the body moves. The feet and body should be heading more back than down.

I am more likely to find people with issues in jumping back into chaturanga. But my data is skewed. The common problems I see include:

– Lower back issues

– SI joint problems

– Shoulder problems

I often see yoga practitioners, and not just beginners, jump back into chaturanga and basically just take advantage of gravity. By this I mean they are not using any strength to resist the effects of gravity. If gravity is taking you down, why fight it? Well, how about control?

By isolating the movements, that is, jumping back into high plank first, you can develop control over this transition. If you’ve been jumping back into chaturanga for some time, it can be quite difficult to jump back to high plank with straight arms. I see this as the first step in redeveloping the pattern of jumping back. The pattern of bending the elbows is just so ingrained it’s difficult to shut it off. The second part of developing the new pattern is the part that many people seem to want to avoid: lowering down into a high quality chaturanga. What is a high quality chaturanga anyway?

In order to control the jump back into chaturanga these two separate patterns need to be in place already. If not, we default into letting gravity do the work for us and we may lose some of the control we really should have.

Developing The Patterns

Jumping back with straight arms does not seem that difficult. It isn’t really, just don’t bend your elbows. What this does though, is force you to use and engage muscles more closely related to the core.

It’s the pattern of lowering down into chaturanga that is even more important. It leads us back to the question, what is a high quality chaturanga anyway?

For me it’s one where the serratus anterior remains engaged. Not to overly complicate it, but when you lower down into chaturanga, it’s your serratus that you’re really after to keep the shoulders in a good place. For instance, when you see that worrisome chaturanga where the shoulders have dipped too low and tilted forward, this shows me a lack of stability in the shoulder girdle.

I know we often say the shoulders have dipped. But that’s non-specific. The shoulder joint itself is where the humerus meets the scapula. The shoulder joint itself does not dip. It’s the scapula that changes position and takes the humerus with it.

When serratus is engaged during the lowering down, it is resisting the movement of the shoulder blades heading toward one another. Don’t get me wrong, they are going to head toward each other in what we call retraction. Although there is sometimes a verbal cue to pull the shoulder blades together, it’s not one I subscribe to. If you do, it’s ok, we can disagree.

What I want, is to resist this action with the serratus which is a powerful protractor (bringing the shoulder blades around the front). When the serratus contracts to resist retraction it is doing what we call an isotonic eccentric contraction. In essence it is contracting and lengthening simultaneously.

With the engagement of serratus anterior comes stability. From that stability in the shoulder girdle you can then focus on isolating the movement of the shoulder and elbow joint. After all, it is these two joints that are lowering you toward the floor. I choose to make this the focus with students and keep the instructions for the shoulder blades simple. That is, that they be stabilized by using the serratus. If the shoulder blades are in their “neutral” place or close to it, then the shoulder joint is in its “neutral” place as well. In essence, nothing is dipped too far forward.

With the shoulder girdle in neutral, the real focus of movement comes into the elbow joint.

This is where the triceps comes into play. As we lower down from a high plank, the triceps is also doing an eccentric contraction. Its contraction is resisting our downward movement. This creates a controlled lowering down. I realize, this isn’t easy for everyone and can take a long time to develop. My point is, develop it on the right foundation, a stable shoulder girdle.

Conclusion

I realise that so far in almost all of these posts I have been focused on the arms. More specifically, I’ve been focused on the serratus, armpit, hand, shoulder relationship. From my point of view, it’s an important pattern of development. Moving forward it’s time to move on from the arms and into upward facing dog. Parts of it are tied to the jump back, the distance that our feet are from our hands, and especially how we head into the yoga posture from our beloved chaturanga.