We talk a lot about “hip-openers” in yoga, but hip-opening is actually more complex than we often realize. In Part 1 of this 2-part article, we’ll examine the anatomy of tight hips and what it truly means to open them.

http://yogadork.com/2014/04/02/lets-forget-about-hip-openers-part-1/ – by Jenni Rawlings

Welcome to Part 1 of my 2-part hip-opening article! In Part 1, we’ll examine the anatomy of tight hips and what it truly means to open them. In Part 2, we’ll discuss some specific hip-opening alignment tips that most yogis are missing in their practice.

Let’s Forget About “Hip-Openers”

We talk a lot about “hip-openers” in yoga, but hip-opening is actually more complex than we often realize. Pigeon pose and its variations are usually considered the main group of poses which “open our hips”, but surprisingly, most people unknowingly practice these poses in a way which bypasses the actual hip-opening they offer. The truth is that nearly all yoga poses are hip-openers, but we haven’t learned to think about them this way, and we therefore don’t align our joints to find this hip-opening potential that our bodies so desperately need.

Instead of thinking about the small group of poses we usually classify as “hip openers”, we should broaden our focus and learn to open our hips throughout our entire yoga practice.

Anatomy Lesson

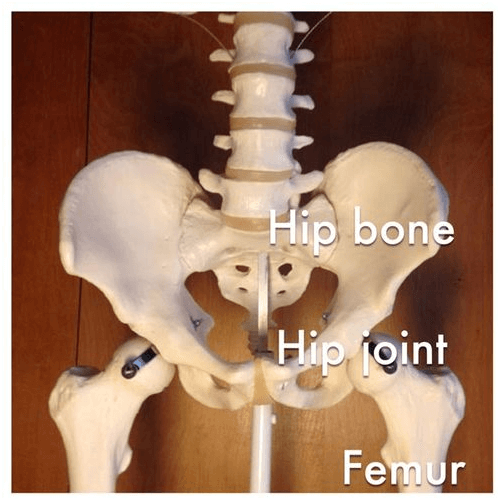

We can all point to the general area of our body we have in mind when we talk about our “hips”. To be specific, though, we can say that the actual hip joint is located where your femur (thighbone) meets your pelvis (hip bone). And for the anatomy geeks in the room, let’s be technical and define the hip joint as the place where the head of the femur (the ball-like prominence at the top end of the bone) articulates with the acetabulum, a concave hemispherical socket located on the side of the pelvis. (Fun fact: did you know that “acetabulum” means “little vinegar cup” in Latin? And are you a new fan of anatomy trivia now?)

The hip is a joint, which means that it’s a moveable part of your body. Motion at the hip takes place when the femur and pelvis move in relation to each other. There are lots of movements available at the hip joint, including hip extension (moving the thigh behind you, as in shalabhasana), hip flexion (think diving forward from tadasana to uttanasana), hip abduction (moving your thigh out to the side, like your back leg in warrior 2), hip adduction (moving the thigh toward your midline – think eagle pose), and internal and external rotation. Ideally all of these motions would be fluid and easy for you all of the time, but all too often, our hip joint movement is restricted in one or more planes (or all of them), resulting in hips we experience as “tight”.

What Does It Mean to Have Tight Hips?

Even though we might casually talk about our joints as being “tight”, the truth is that your joint itself isn’t really the issue. It’s actually the muscles and fascia that cross your joint that restrict your movement. And how do these tissues become tight? As my biomechanics teacher Katy Bowman says, “your body adapts to what you do most frequently”. And the one body position that we as a culture tend to assume most frequently is sitting with our hips and knees flexed at 90 degrees. Even if you don’t think you sit a lot, or if you have a job which requires you to stand, you’re probably forgetting all the other time you do spend sitting because it’s so ingrained in your daily lifestyle that you almost don’t even realize it.

In a nutshell, our over-use of the sitting posture shortens the muscles that cross the front of our hips (hip flexors) and the muscles that line the back our thighs (hamstrings), as well as effectively “turns off” our otherwise powerful glutes, and basically just throws our whole hip package out of balance. The result is unhappy, tight hips which drive us into yoga classes in search of some much-needed opening.

Why is Having Tight Hips Uncool?

There are many reasons that our tight hips are uncool, and the general discomfort we experience from stiff, unyielding muscles is just the beginning. Most people don’t realize the incredibly huge role that our musculoskeletal system plays in our body’s overall health. But our blood vessels and lymphatic vessels are embedded inside our muscles. Blood carries the oxygen which feeds our cells, resulting in cellular regeneration, and lymph is our body’s waste-removal system. But blood and lymph can only flow through muscles which are at their optimal, supple length. A tight muscle will resist the circulation of these vital fluids – picture a fist gripping a hose and how that would effect the flow of water running through that hose. Put another way, tight muscles work against the flow of your cardiovascular system (blood) and your immune system (which your lymphatic system supports). The result is increased blood pressure, decreased metabolism, waste accumulation in your tissues, and increased risk of cardiovascular disease. If optimal health in our body is important to us, bringing suppleness and circulation back to our tight muscles must be a priority. Had you ever thought about your muscles from this bigger-picture, whole body health perspective?

Another reason that tight hips are no good is that when we want to get something done that requires hip motion, like picking something up off the floor, or pressing up into urdhva dhanurasana (wheel pose) in yoga, we will move from somewhere else more than we should because we can’t move from our hips as much as we should. Unfortunately, the alternative body part that is all too often over-used when our hips are tight is our vulnerable spine. Hello, spinal joint degeneration, herniated discs, impinged nerves, and back pain in general!

Understanding a bit more about our anatomy reveals to us that tight hips are actually about much more than the inconvenience you might experience when you can’t get into lotus position in yoga class.

What Does “Opening the Hips” Mean?

For much of my yoga-practicing career, I was under the impression that if you wanted to open your hips, you basically just needed to do pigeon pose a lot, and that pretty much summed up all you need to know about hip opening. 🙂

But hip-opening is about so much more than simply pigeon pose. There are a total of 22 muscles that cross the hip on all sides and at varying angles, including your hip flexors in the front, your hamstrings, glutes, and deep lateral rotators in the back, your inner thigh muscles (collectively called your “adductors”), and your outer thigh muscles (collectively called your “abductors”).

A “hip-opener” is technically any stretch that lengthens any of the 22 muscles that cross the hip. This means, for example, that all hamstring stretches are hip openers, all inner thigh stretches (think baddha konasana) are hip-openers, all standing poses (warriors, lunges, etc.) are hip-openers, many of yoga’s twists are hip-openers, and as counterintuitive as it may seem, all backbends are also hip-openers. (Crazy, huh?)

Can you see that once we have an anatomical definition for what hip-opening is, it’s difficult to name a yoga pose which is not a hip-opener? (Inversions aren’t really hip-openers, but I wish they were! 🙂 ) Our whole yoga practice is basically just one big hip-opening opportunity.

However, most yogis are very (very!) good at compromising the work we need to do in order to stretch our hips in our poses. This is because we simply don’t understand how to position our joints (a.k.a. alignment) in a way that actually stretches our hips, and we end up leaving our mat without much change in our tight hips at all.

But it doesn’t have to be this way, guys! Stay tuned for Part 2 for some great tips on refining your practice with hip-opening in mind!